Polish Londoner

These are the thoughts and moods of a born Londoner who is proud of his Polish roots.

Thursday 14 December 2017

EU citizens’ rights – two realities

As UK citizens slowly absorbed the overnight shock of the referendum result on June 23rd, 2016 and contemplated the extraordinary potential consequences, including an independent Scotland, uncertainty over the Irish border, the future of the economy, the fall of the pound, the triumph of nationalism, the one factor that seemed to remain stable was the fate of the EU citizens in the UK. After all, most of the Leave campaigners Farage, Gove, Johnson had all stressed that the EU citizens who were already here would not have to depart. It was like a constant repetitive mantra: “all EU citizens are safe”. And overwhelmingly many EU citizens, whether from Western, Southern or Eastern Europe firmly believed that. “We can stay; they need us; nobody will throw us out”. Even the sudden explosion of hate crimes against Poles and others in the 3-month aftermath after Brexit did not shake that feeling. Within 2 weeks of the referendum, on July 6th Andy Burnham, Labour MP introduced a motion in Parliament confirming that the rights of EU citizens would be retained in full. The vote at 245 to 2 was almost unanimous in favour and Boris Johnson also spoke eloquently in its favour. However, the vote was not binding on the government and the then Home Secretary Theresa May made clear that EU citizens’ rights can only be guaranteed when the EU was ready to respect the existing rights of UK citizens abroad. Weeks later she was Prime Minister, Boris Johnson became Foreign Secretary and the EU citizens became a hostage in the diplomatic poker game between the UK government and the EU. Although some EU governments made clear that UK citizens’ rights in their countries would be respected the EU Commission and the Council of Ministers refused to be drawn saying all issues can only be discussed once the Prime Minister invoked Article 50. The tabloids laid the blame for not ensuring EU citizens’ rights firmly on the EU although the principle that they be allowed to stay remained unchallenged.

In view of that it seemed like an opportunity for the Government to draw up a detailed plan on how EU citizens’ rights could be preserved on the assumption that the EU would eventually reciprocate it for UK citizens in the UK. Opposition parties and new pressure groups like the3million, New Europeans urged this on the government. In December 40 prominent UK citizens of Polish extraction published a letter urging this in the parliamentary house magazine. Even if some of the details of such a proposal could have been challenged or improved in the negotiations, at least the UK government could have set the agenda on this issue and could show it was not treating EU citizens as hostages or bargaining chips. After all, Brexit was a UK initiative and it was therefore the UK government’s responsibility, and not that of the EU, to initiate positive reassurance to EU citizens, to British businesses, to EU governments (and not least to UK citizens abroad who were expecting whatever the UK proposed for EU citizens to be reciprocated by the EU countries) and reduce the inflammatory atmosphere that had caused UK-EU relations to deteriorate so badly at this time. Furthermore, the issue of retaining existing EU citizens’ rights was generally acceptable to the electorate in numerous opinion polls, even with those wanting to introduce more immigration control after Brexit.

Yet Theresa May, whether as Home Secretary or later as PM, did not choose that option, continued to talk about the need first for the EU to show reciprocity and stoked up public opinion towards the policy of a hard Brexit. As a Remainer she needed to reassure her Brexit-dominated Party and her Cabinet colleagues that she was a keen new convert to the idea of a hard Brexit and sought to unite her party around that posed stance. This was the period before the general election when she reiterated various phrases such as “Brexit is Brexit”, “red, white and blue” Brexit and “strong and stable government” as a camouflage for a lack of clear detailed policy on Brexit while she sought to ram through any negotiations without even consulting Parliament. She had also allowed Home Office officials to broaden the “hostile environment” which she had publicly announced in 2010 as the regime that would be applied to illegal immigrants, so that it would also cover more vulnerable EU citizens, particularly in relation to failed applicants for permanent residence. This was the period when EU citizens, from Western or Eastern Europe, found that their application for PR status required details of every foreign trip over the whole period of their stay (in some cases for 30 or more years), instead of just the required 5-year period required by the EU. The UK authorities needed full details on employment and income and confirmation, where necessary, of having comprehensive sickness insurance (CSI), which should have been superfluous where all had access to a free NHS. If, for whatever trite reason, the application was refused, then hundreds of EU citizens would receive notices of deportation (often later withdrawn), although they had British families here and may have lived and worked here for decades. Yet all this time she assured Polish community leaders and EU governments that she wanted to safeguard the rights of Poles and other EU citizens in this country.

Following a challenge in the Supreme Court in December the Government had to acknowledge eventually that they would need to consult Parliament before starting the process of leaving the EU and that the referendum mandate on its own was not enough. In March 29th of this year, having got her vote through Parliament, she finally invoked Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty and then called a general election, in order to strengthen her majority. Ironically, she lost many seats and now had to lead a coalition government with the support of the Democratic Unionists. This made her position more precarious and therefore caused her to be more stubborn, to promise various red lines, simply to keep her coalition together.

Consequently, when the EU negotiators had made clear that EU citizens’ rights was one of the three issues which needed to be resolved before negotiations could move on to issues such as trade and a possible transition period, they then published their negotiating position which included the requirement that in future all EU citizens at present in the UK should be assured of retaining the same rights, including pensions and access to the NHS, as before for their lifetime and that of their children, including the right not to have their families separated and the right to retain their status even if they had left the UK for a period of time. The right to stay for those with PR or who have eligibility for PR would be automatically registered and any appeal process would be supervised by the European Court of Justice. The EU offer was not perfect as it failed to ensure the rights of UK citizens to travel and work in more than one EU country and could not guarantee voting rights for UK citizens in EU countries, but it was able to offer most of these rights on a reciprocal basis for EU and UK citizens alike.

Instead of responding to this proposition the UK government was anxious to display that it was now a sovereign state and eventually in June it came out with its own alternative proposal using the term settled status, which until now was the equivalent of indefinite leave to remain. It offered EU citizens who had lived and worked here for more than 5 years the right to stay and work in this country with their families, with entitlement to NHS treatment, most benefits and UK pension rights, while those who would have arrived here more recently before an unidentified, as yet, cut-off date would be able to apply for settled status after the requisite 5 years had been served. Also, the much criticized CSI condition was now to be abolished. Mrs May described this as a generous offer and she wrote to the3million that “our intention is to make sure that no one who has made their home in this country will have to leave, that families will be able to stay together, and that people can go on living their lives as before”. Pressure groups like the3million and New Europeans, as well as EU governments disagreed. For instance, it was now necessary for all those who had previously laboriously achieved PR status to reapply for the new settled status, families could not be guaranteed to stay together if still abroad after the unnamed cut-off date or if the family member was a non-EU citizen and the provision of the status as well as its interpretation would be subject to Immigration Rules. Nor was it clear how up to 3 million EU citizens were to be registered over a period of 2 years (i.e. some 4000 a day) with all subjected to criminal records, when the PR registration service had already completely collapsed.

Furthermore, away from the reality of optimistic declarations by ministers and officials, there was still a second reality where more than 5000 EU citizens had already been deported against their will, where Polish and other vulnerable EU citizens, mostly East Europeans, were being detained for indeterminate periods, sometimes more than a year, in detention centres, following decisions by Home Office officials, where equally vulnerable EU citizens were initially being denied free NHS treatment and chased by court bailiffs for unpaid NHS bills, employers and landlords were starting to discriminate against EU citizens and home loans were being denied to EU citizens. Consequently, EU commissioners made clear over the six rounds of negotiation that the UK offer was nowhere near good enough.

And slowly over those 6 rounds of negotiations between June and November the process of extracting more reasonable concessions was like pulling teeth from a divided and disorientated UK cabinet. Thus low and intermittent income for self-employed would no longer become a criterion for refusal, cost of renewing settled status for those already registered for PR would be free of charge and require only evidence of residence or lack of criminal record, UK judges could hear appeals based on EU law, Immigration Rules would no longer apply and special status criteria would be based directly on the terms of the final Withdrawal Agreement, future family members, including future children, would now be covered by settled status, past criminality where sentence was completed would no longer be a bar to settled status. However up to and until December many issues remained unresolved as the cabinet battled internally over supposed red lines such as European Court jurisdiction, child benefit paid to children still abroad, and the right for all EU families to unite after the Brexit deadline, even though British citizens had no such rights. The cut-off date was now fixed on the same day as Brexit, i.e. at 29th March 2019. Every concession followed intense lobbying by pressure groups and renewed meetings on improved systems. Also, the Home Office has been consulting local communities, and specifically the Polish community at conferences in London, Birmingham and Edinburgh, where it was made clear that the previous Home Office culture of creating a “hostile environment” would be changed, that settled status would be merely swapped for PR status and that local organizations could assist in testing pilot schemes for a new simplified online system for registration.

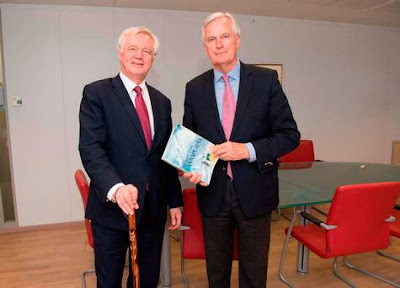

Of course, the rollercoaster negotiations in the first week of December, finalizing the issues of the financial settlement and the Irish border may have left the European citizens issue on the side-lines but some key final agreements were made here too which were published in a Joint Statement by the EU and UK negotiators.

Following that publication, the current position on EU rights was presented by the Home Office as follows:

EU citizens who arrive here by March 29th, 2019 and have been continuously and lawfully living here for 5 years will be able to stay indefinitely by getting settled status, so they will be free to live here, work or study, have access to public funds and services, including healthcare and pensions, and go on to apply for UK citizenship. If they have not been here for 5 years they can apply for a temporary residence permit to work off that period until they reach the 5-year threshold and then apply for settled status. Close family members and dependents already here can also apply for settled status, while those who arrive later, while still in that relationship, would also be allowed to stay. This includes spouses, registered partners, parents, grandparents, children, grandchildren and persons in a durable relationship. Grounds for refusal would only be those quoted in the mutually agreed Withdrawal Agreement, i.e. a residency and criminality check. CSI will no longer be a criterion for refusing settled status but could still be invokes in relation to students or self-sufficient EU citizens seeking access to a free health service.

The Home Office promise that they will apply a more user-friendly application system for settled status, where some of the information will already have been obtained from HMRC or the DWP, missing documents or mistaken responses could still be rectified without rejection. Applicants will be required to provide an identity document with a recent photo and to declare any criminal convictions. For existing PR holders, the application will be free of charge, for others it will be the equivalent to the cost of applying for a passport. Applications could start in 2018 before Brexit and need to be completed within 2 years. Successful applicants will receive a new settled status document. All applicants can stay in the UK until their status is approved or rejected. If EU citizens had already obtained indefinite leave to remain earlier they need not make any further applications, but could also apply for a biometric residence permit if they wish or swap their status for the slightly superior settled status free of charge.

If an EU citizen arrives here after 29th March 2019 but during the 2-year transition period that person will still initially be allowed to live, work and study here but many of the rules are still subject o negotiation in phase 2 of the negotiations in 2018. For all those arriving after the end of the transition period their status will be subject to immigration rules to be decided by parliament after the publication of the Independent Migration Advisory Committee report in July 2018.

What the current Home Office guidelines did not make clear, just as Mrs May made no mention of it in her speech at the December 8th morning press conference in Brussels, was that “the competence of the Court of Justice of the European Union should be preserved with regard to the consistent interpretation and application of the citizens’ rights set out in the Withdrawal Agreement.” This means that over the next 8 years the UK tribunals should be able to ask the European Court for interpretation of rights which may still seem unclear. The decision to make such a referral lies within the competence of the UK court or tribunal.

There are further details in the Joint Agreement of the EU and UK negotiators which are not mentioned in the Home Office summary. This agreement also covers EU workers who live in one state and commute daily to another state. Any decision on granting settled status should always give the benefit of the doubt to the applicant, whereas currently it is always in the hands of the Home Office official. Also, persons who absented themselves from the UK after acquiring permanent residence do not lose their residency rights unless they fail to return in 5 years. The European Health Insurance card continues to function. There is to be no discrimination in jobs or health care provision for EU citizens. A Withdrawal Agreement and Implementation Bill will be introduced into the UK parliament to implement all that has been included in the Withdrawal Agreement, including all chapters on citizens’ rights. Significantly, the Joint Report refers only to “Special Status”, not “settled status” and a similar wording appears in EU Commission’s Report to the Council of Ministers.

Also, a number of issues are still to be resolved in the Second Phase of the negotiations. These include the rights of nearest relatives to join EU citizens in the UK who were not related at time of departure, voting rights in local elections, mutual recognition of academic and professional qualifications, and the method of monitoring the application and implementation citizens’ rights by an independent national authority which can receive appeals from EU citizens.

Just as the ultimate arbiter of the financial negotiations was the European Commission and for the Irish border agreement was the Irish government, the ultimate arbiter on citizens’ rights is the European Parliament. It is possible that on December 13th the European Parliament may exercise its displeasure on several issues with regard to the Joint Report which will be presented in the coming week to the Council of Ministers.

Firstly, the Parliament wanted the registration to cover confirmation of existing rights, rather than an application for these same rights. This is still not clear from the final document although the universal introduction of criminal checks suggests that these will indeed be fresh applications, even if only described as a “swap”. Also, they had urged that future family rights for those not yet in a relationship should be assured as well and that the ECJ should have a more active and a permanent jurisdiction rather than just on the current temporary passive basis. The3million was also pushing for these issues, along with a more permanent supervisory role for the European Court of Justice but these would be difficult to implement now. However, it would be advisable for the Home Office to change the name of settled status as it could be misleading for citizens, police and legal bodies alike to have a separate meaning for settled status for EU citizens and for non-EU citizens, and would undermine the bespoke nature of the offered status for EU citizens. It would still be preferable to refer to some kind of UK version of permanent residence which could more easily be reciprocated in the EU for UK citizens.

While many may feel satisfied with the current agreement it has to be remembered that the alternative reality is still in existence. While the Home Office is promising to change its culture in time for Brexit it is still not changing its current culture. Recent suicides and attempted suicides by EU citizens facing deportation either at home or in detention centres is high. Current procedures with regard to expulsions of EU citizens should be in accordance with EU Directive 2004/38/EC, which refers only to the deportation of those who are a serious current threat to society or to security. Yet Poles who have families here have been deported for minor crimes past and present such as drunkenness or cheating on a tachograph, regardless of whether they have family here with children. “The Guardian” has reported how Polish fathers have been arrested and deported for a past crime in Poland after they complained to the police about being harassed and intimidated by neighbours or employers. There is considerable hostility still to East Europeans in the job centres, local government offices, health trusts and police stations in provincial Britain where at any excuse Poles have been told to consider returning to their own country. If there is this much uncertainty and hostility now while the UK is still a member of the EU, how much worse can it get after Brexit? Without supervision by the European Court of Justice, what is to prevent a future hostile government to repeal the Withdrawal Agreement and Implementation Act?

For those reasons it is still wise to consider retaining active and permanent monitoring by a European body with clout like the European Parliament, so that whatever is agreed on paper may still not give sufficient guarantees to Polish and other citizens and their families about the future.

Wiktor Moszczynski London 12th December 2017

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)